NucleusAI Migrated 1.5B Objects from S3 to GCS in under 96 hours

2026-02-12

Most migration writeups optimize for copy throughput.

Ours optimized for dataset correctness under transformation. While moving the bytes, we rewrote the dataset’s metadata contract, validated payloads, and emitted replayable failure ledgers without turning the operation into weeks of manual tail-chasing.

At 1.5B objects, we negotiated with request throttles, TLS handshakes, file descriptor limits, and tail failure distributions.

This post is a deep walkthrough of the system we built. A Parquet-level control plane that compiled work units, and a data plane that executed a high-concurrency download → validate → upload protocol with machine-readable progress.

1. The Framing: Migration as a Compiler

We stopped thinking in terms of objects and started thinking in compilation units.

A metadata Parquet was the unit where schema, validation, layout, and replay semantics had to be true. This mattered at billion-object scale because "eventual correctness" implemented as scattered logs and manual reruns didn't converge. Throughout the migration process, assets were moved out of the source system and systematically passed into an online integrity gate where dead links, pixel garbage, non-images, corrupted assets, and outlier histograms were weeded out.

For each metadata Parquet, three artifacts were produced upon completion:

- Data objects in GCS, written under a deterministic prefix with optional shard fan-out for key distribution.

- A renewed metadata Parquet where updated URIs were derived from the exact mappings emitted by the worker run.

- A failure ledger that supported targeted replay listing the missing IDs and a reason-coded explanation.

This allowed us to achieve the following operational and performance invariants throughout the process.

Operational invariants

- Idempotent by unit-of-work: re-runs did not do duplicate work.

- Replayable tails: failures were isolated at Parquet granularity with enough information to retry only the failures.

- Observable: progress was measured without SSH’ing into VMs or log tailing.

Performance invariants

- Sustained throughput: peak throughput mattered less than stable tail latency and sustained transfer rate.

- No retry storms: backoffs were bounded and failures were classified.

- Key-space should scale: avoided prefix hot-spotting by enforcing hierarchical structure and hash based fan-out.

Any tooling choice had to optimize for those invariants, not for accessibility and copy throughputs in isolation.

2. Tooling Choice: We Didn’t Use Storage Transfer Service (STS)

Storage Transfer Service (STS) is excellent when the problem is primarily copying bytes reliably at scale, and Google’s own guidance focuses on operational tuning for large managed transfers. Our problem required that transfer, validation, and metadata materialization be a single correctness pipeline, not three disconnected jobs stitched together by humans and heuristics.

Our workers rejected assets at ingress using cheap, effective validation gates and emitted discards as first-class events. Because the control plane consumed those events to flag bad_image and decide which IDs got renewed URIs, correctness was enforced by construction. Metadata could not claim an object migrated successfully unless the data plane emitted UP_OK.

Why we rejected “STS + Post-Processing"

An obvious counterproposal was to copy everything first, then run a separate validator followed by metadata rewrite, and finally relayout the objects into the final key-space. At our scale, this would create a new harder system for reconcilation.

- Renewed metadata must reflect exactly which objects were valid and present. If validation was decoupled from transfer, we would need a second join system to reconcile transfer results with metadata rows. We chose to collapse this join into a single event protocol that could mint a destination key only at a succeful upload.

- Listing and scanning the destination key-space at billion scale would be slow, expensive, and failure-prone under throttling.

- Copying bad-assets first and deleting later would burn egress/ingress and request budgets on data which was intended to be filtered.

- When failures are spread across multiple independent systems, you lose the ability to re-run one Parquet and know you’ve repaired that unit’s contract.

In addition, we wrote a new naming scheme with shard prefixes derived from SHA1(id) so that writes/reads distribute under a common prefix. This matches Cloud Storage’s guidance that sequential names can slow autoscaling and that randomized prefixes help distribute load and ramp request rates.

The Decision Summary

| Requirement | Google Managed Transfer (STS) | Our Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Bitwise copy, incremental sync | Strong | Strong |

| Validate payloads (decode/type/size) during transfer | Weak | Strong |

| Rewrite object key-space for future read QPS | Limited | Strong |

| Write back transformed metadata Parquets | Not Native | Strong |

| Per-unit failure ledger + targeted replay | Limited | Strong |

| Progress as a protocol (structured, machine-readable) | Limited | Strong |

3. Architecture Overview

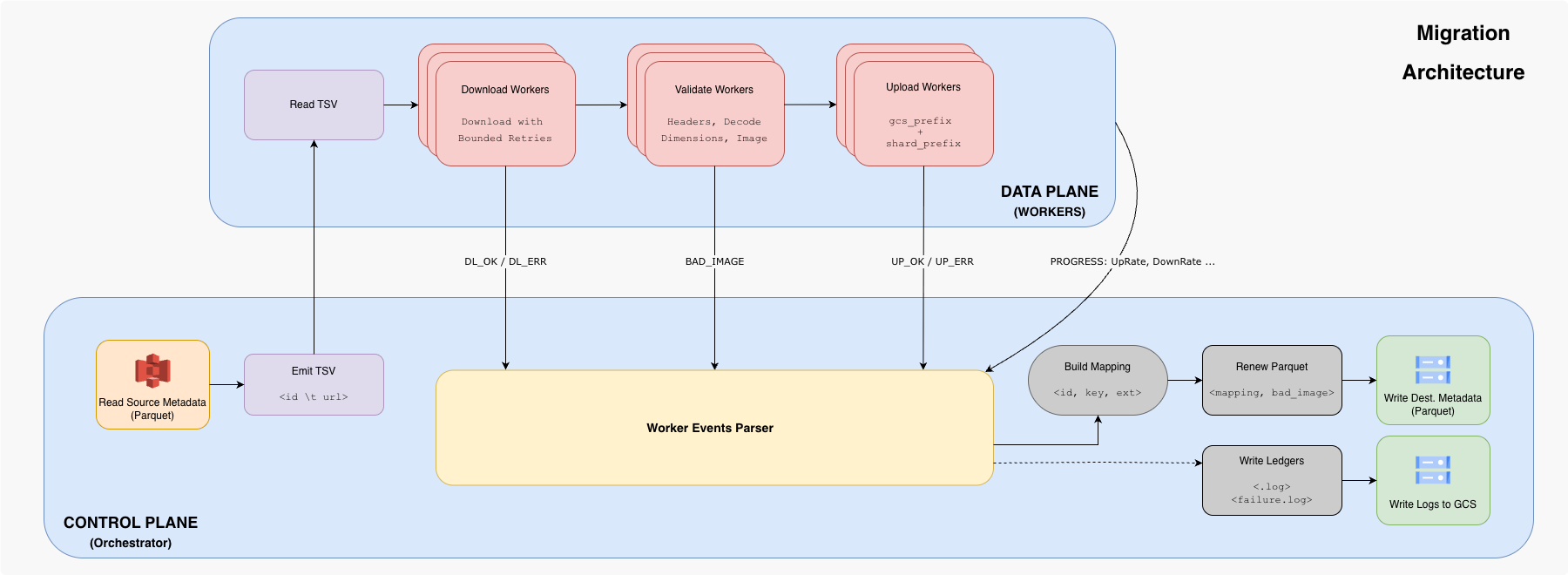

We operated the whole program at two levels-

- Control plane compiled and managed the workers, events, ledgers and renewed Parquets.

- Data plane executed the high-concurrency transfer protocol

3.1 Control Plane: Parquet-level Orchestration and Idempotency

The orchestrator read Parquets from S3, generated a TSV, ran the downloader binary, and wrote the updated Parquet to the destination metadata bucket using PyArrow. To maintain idempotency, it shortlisted tasks by checking whether destination Parquets already existed and supported resumability via a JSON manifest.

We kept the unit of work as the Parquets. This design choice made the tail manageable. Each Parquet was a batch contract with its own completion criteria, its own logs, and its own replay handle. We never "retry the migration", rather we "recompile Parquet X with failures-only input."

The TSV tasks (id, url) were kept minimal for stability and progress, success mappings, and failure taxonomy came back as a structured event protocol that we parsed deterministically.

for Parquet in list_source_parquets(): if already_processed(Parquet): continue df = read_parquet(Parquet) # contains (id, media_path, ...) tsv = write_tsv(df[["id", "media_path"]]) # (id \t url) events = run_worker(tsv, concurrency=K) # emits DL_*/UP_* and PROGRESS mapping, failures = materialize(events) df["bad_image"] = df["id"].isin(failures.bad_image_ids) df["updated_media_path"] = df["id"].map(mapping.get) upload_parquet(df, destination_meta_path(Parquet)) upload_failure_ledgers(failures, destination_log_path(Parquet))

3.2 Data Plane: High Concurrency Workers

The workers emitted machine-readable events:

DL_OK <id>andDL_ERR <id> <reason>for all download outcomes.BAD_IMAGE <id> <reason>when validation failed (treated as a classified failure, not a transient error).UP_OK <id> <key> <ext>andUP_ERR <id> <reason>for upload outcomes, where<key>is the deterministic destination object key.PROGRESSlines every ~5 seconds with counters and approximate rates that the orchestrator parsed to update a live progress view.

We treated worker output as an API. stdout carried per-item facts (DL_OK, BAD_IMAGE, UP_OK etc.), while stderr carried aggregate telemetry (PROGRESS ... UpRate DownRate ...) so orchestration could be robust without parsing logs. This events as interface choice was what let us swap orchestration behavior (dashboards, retries, resumability) without touching transfer logic.

for _, task := range tasks { bytes := download(task.url) // with retries (bounded, jittered) validate(bytes) // header, content-type, decode etc key, ext := uploadToGCS(bytes) emit UP_OK(task.id, key, ext) or UP_ERR(task.id, reason) }

We front-loaded connection hygiene. A custom HTTP transport capped per-host concurrency and reused keep-alive connections (high idle conn limits, per-host caps), and we set hard timeouts so dead servers didn’t pin goroutines. Retries were intentionally bounded (maxRetries) with jitter and a strict retriable classifier.

Validation Gates

We used a set of cheap gates that eliminated the worst garbage early:

- Content-type sanity: rejected obvious non-image payloads.

- Magic byte / header sanity: rejected payloads that aren’t image-shaped.

- Size sanity: rejected empty bodies and capped maximum size to avoid pathological payloads.

- Decode + dimensions: verified decodability and enforced a minimum dimension floor.

An aerial view into the entire architecture is given in the following flowchart.

4. Storage Layout

The uploader chose an extension by inspecting header bytes and set the corresponding content-type on the GCS writer. We optimized for uniform key distribution which led to predictable parallel read throughputs and shardable training access patterns.

We placed objects under a deterministic prefix:

<gcs_prefix>/<shard_prefix>/<id>.<ext>

Where:

<gcs_prefix>is derived from the metadata batch identity (e.g., sub-bucket + folder + Parquet number)<shard_prefix>is a short hex prefix derived fromhash(id)to fan out keys.

The shard prefix was the cheapest way to buy parallelism without changing readers. We picked shard width so that a single Parquet could be read by workers with minimal prefix contention, and the mapping stayed deterministic because it was computed from the ID hash. Thus, it let the training pipeline to scale without dataloaders fighting for prefixes, aligning with Cloud Storage’s official guidance on even access distribution and randomized naming.

5. Failure Taxonomy + Replay

At our scale, a "100% success rate" was not the first goal. It was to make forward progress while isolating and explaining failures.

We classified failures into categories that had different handling:

- Dead link / missing object: permanent failure and logged for metadata repair.

- Invalid payload (non-image, corrupt, too small): marked and excluded from training.

- Transient download errors: retry bounded and logged if exhausted.

- Transient upload errors: retry bounded and logged if exhausted.

For each Parquet, the failure ledger included:

- A summary log of failed IDs

- A detailed log:

(id, reason_code)for replay and debugging

6. Observability and Visualization

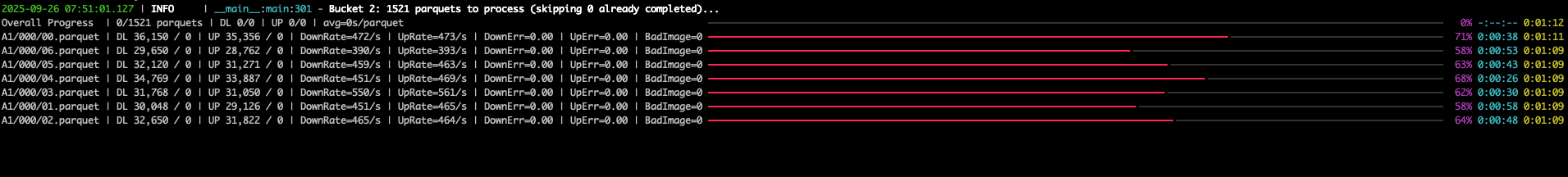

Instead of scraping logs, we made progress reporting an explicit protocol:

- The workers emit

PROGRESS UpRate=... DownRate=... DownErr=... UpErr=...lines for downloads and uploads. - The orchestrator consumes them and renders a live dashboard (rates + error ratios)

That gave us:

- safe concurrency tuning during ramp-up

- early warning on throttling or failure spikes

- per-bucket and per-Parquet completion predictability

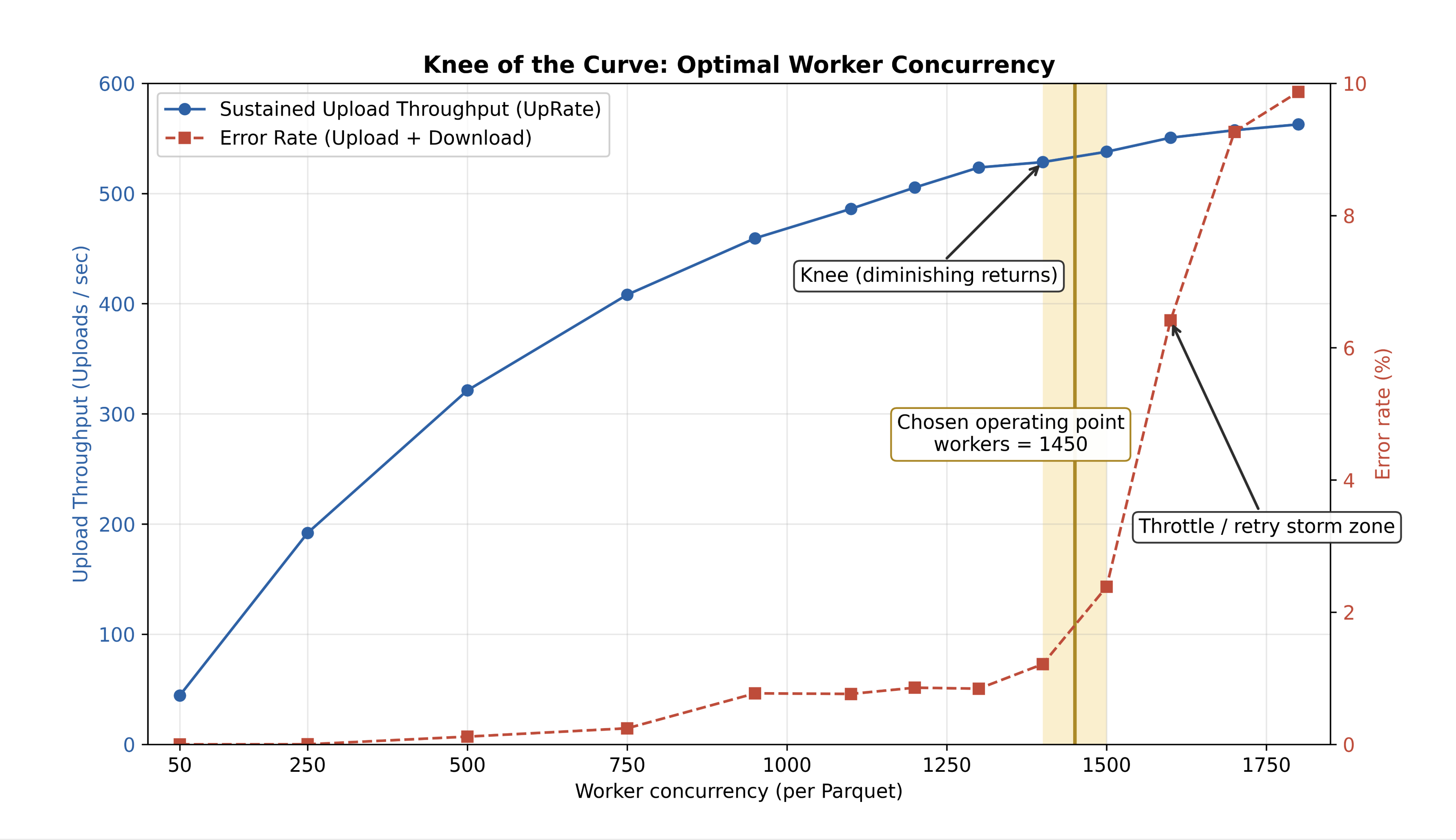

We aligned our tuning loop with standard operating processes. We ramped concurrency until error rates climbed (often 429/5xx), then backed off to the knee of the curve (see Appendix) and held for the remaining migration. Because the workers emitted PROGRESS every ~5 seconds, we could do this live without waiting for external dashboards to catch up.

Appendix

We tuned the worker count by ramping concurrency and plotting sustained throughput (UpRate) against the combined error rate derived from the worker's PROGRESS telemetry.

The knee was the point where additional workers produced diminishing throughput gains while error rates started to climb sharply, so we held the fleet at ~1450 workers/Parquet for a stable long-haul run.

This gave us a predictable operating regime with high steady-state throughput without entering the throttle/retry-storm zone.